Tag Archives: nostalgia

The Case of the Rattling Awl

The first car I remember my parents owning was a 1977 Chevrolet station wagon—blue, with fake wood paneling on the sides. A few months after buying the car, Dad reports, something within the passenger-side rear compartment wall, near the spare tire stowage, began to rattle. Soon, the noise irritated him enough that he disassembled the interior paneling to find and silence it.

Which is where he discovered this tool, a hand awl, presumably lost or abandoned there by an upholstery installer on the assembly line. Dad, who has never been a big fan of organized labor, at least once advocated the latter theory, i.e. that the awl was abandoned in the car, on purpose, by a worker exploiting union regs to the effect that he or she could not be required to work unless provided with the correct tool. Being considerably more liberal, I am prepared to give that long-ago UAW member the benefit of the doubt and believe it was walled up by accident.

Dad put the awl in the top drawer of his toolbox and it’s lived there ever since, though the car it came in is now thirty years gone. It’s heavy, solid, and quite well made, with a turned aluminum handle and replaceable pommel- and tip-fittings. I used it just today.

Knowing where to drill is most of the bill

My Dad, who has been an electrical engineer for 40-odd years, likes to tell this apocryphal story about Charles Proteus Steinmetz, the famous German-American engineer who, in the early days of General Electric, was a pioneer in the development of alternating current technologies, specifically power transmission and A/C electric motors:

Late in Steinmetz’ life, he was called in to consult on a vibration problem in a newly-installed piece of large, rotating machinery at a major factory. Steinmetz—who was afflicted with dwarfism, hunchback, and hip dysplasia, and stood only 4’3″ tall—looked over the blueprints for the machinery, examined it, took measurements, scratched figures.

“Bring me a drill,” he said, eventually, “with a one-inch bit.”

So tooled, he climbed up on a large electric motor, located just the right spot, and drilled a single hole in the casing.

“That,” he said, “should fix it.”

And, of course, it did. The machinery turned smoothly, everyone shook the great man’s hand, and he departed.

Weeks later, the management received a bill for $10,000. Steinmetz died in 1923; using that year as a base and adjusting for inflation gives just over $125,000 in 2010 dollars—a princely sum for a few hours’ work. Chagrined, the company responded with a respectful request for an itemized invoice. To which, the story goes, they received the following reply:

Drilling hole in motor casing: $2.00

Knowing where to drill hole: $9,998.00

TOTAL: $10,000.00

That thing that Joey read

I graduated from Richardson High School in 1994. Graduating with me that year was Joseph Belasco, who went by Joe or Joey, though I think he’d grown to dislike the latter by the time we were seniors. I remember him appearing at Westwood Junior High when we were in eighth grade, having moved or transferred from some distant place. From then until the Richardson Independent School District was done with us, Joe and I were peers. Not friends, but peers.

Senior year, ’94, we were both National Merit semifinalists. There were nine semifinalists, altogether, and though sharing that distinction did not overcome our natural, teenage cliqueishness, there was a bond. We shared many of the same advanced placement classes, notably Cindy Whitenight’s Literature and Creative Writing. In one of them—Creative Writing, I think—we were tasked to bring in a favorite piece of another writer’s prose to read aloud.

Joe chose a passage from Dennis Leary’s then-popular book No Cure For Cancer. This is it:

On my brother’s tenth birthday—I was six—we had a little birthday party. Just me, my brother, and my mom. And a chocolate cake. And little birthday hats. Singing the birthday song. “Happy birthday to you! Happy birthday to you!”

My dad was putting paneling in the living room during the ten minutes we weren’t in there. He was working with a circular saw. So this was the sound effect we heard come echoing down the hallway during the birthday song: “Happy birthday to you. Happy birth–”Zzzazow zzzazow zzzzzazazazow zzzzzazazow THA-THINK

And my dad comes waltzìng gingerly into the kitchen with his thumb hanging off at the bone. We’re sitting there in our paper hats with chocolate cake in front of us—our faces frozen in fear. I’m thinking, “Wow. Dad’s thumb is hanging off. Look at all that blood. Look at the bones. He’s probably gonna start crying any second now.”

And this is what my father says—his thumb is literally hanging by a thread of a bone, there’s blood everywhere, and he says—and I quote, “We got any tape around here? I need to tape this baby up.” My mother snapped. She starts screaming, “I’ll drive you to the hospital! Call the hospital! Tell them we’re coming! Ahhhh!” But he wouldn’t let my mother drive him to the hospital. That was too much of a threat to his masculinity—to be seen in a car driven by a woman. So he taped up his thumb with black electrical tape and drove himself—mínus one thumb—to the hospital. Never blinked an eye. He was humming as he taped it up in front of us.

We’re sitting at the table—paper hats, chocolate cake, blood, bits of bone. I looked at my brother and said, “Hey, pal. Forget about crying. Crying is over. We’re never going to be able to cry about anything ever, okay?” Our authority figure is a man who could sever his own head with a chainsaw, and he’d staple-gun it back on: PUN-CHIT! PUN-CHIT PUN-CHIT PUN-CHIT! “Fuckin’ head came off!”

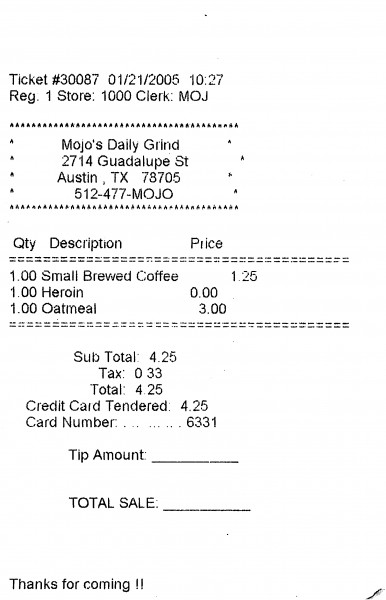

Joe died at the end of 1996, around the time of my twenty-first birthday. Close friends reported an accident involving heroin. I don’t know as much as I should about him, either his life or his death, but I know that he read these words aloud to his friends, and his peers, sometime in the spring of 1994, and made all of us laugh together.

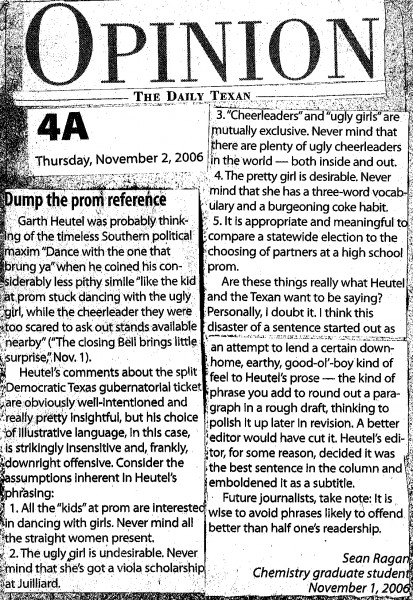

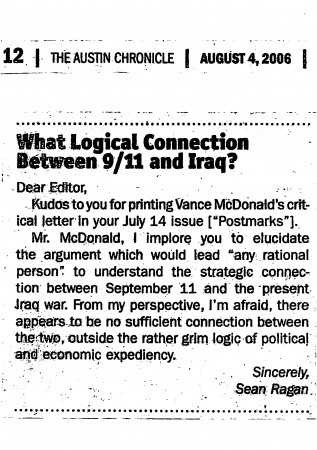

Letters to editors

Clippings from my files suggest an observable trend: The more miserable my life, the more likely I am to take it out on the local newspaper editors. These two date from the same year. I was just starting grad school, and probably should’ve been making black sludge into brown sludge on a flash chromatography column, somewhere, instead of inveighing against sexist language (above) and neoconservative foreign policy (below). But there’s no doubt which was more enjoyable.

My favorite spray bottle

I have had this clear blue, spherical, plastic misting bottle for twelve or thirteen years. I remember paying $8.99 for it at Target, I think, in 1998 or 1999. It was one of the first objects that ever made me pay attention to product design as an aesthetic activity. I went through a period thereafter where I was infatuated with expensive mid-century “modern” design and furniture, and bought some stuff in that vein. But all that snobby crap is gone, now. My $9 spray bottle remains.

I actually upgraded it, slightly, at some point, by replacing the “factory” rigid plastic suction tube with a piece of flexible vinyl R/C model fuel line with a brass R/C fuel filter at the end. This mod was a significant improvement, because the flexible, weighted line seeks the lowest point in the reservoir and so continues to draw water even when the sprayer is held at odd angles. Plus, the fuel filter helps keep grit and dust out of the sprayer mechanism, and hopefully prolongs its life.

I’ve recently discovered the brand name is “Tolco Mistaround.” They were manufactured in blue, red, green, and “smoke.” Though a bit hard to find, they are still for sale here and there on the web.

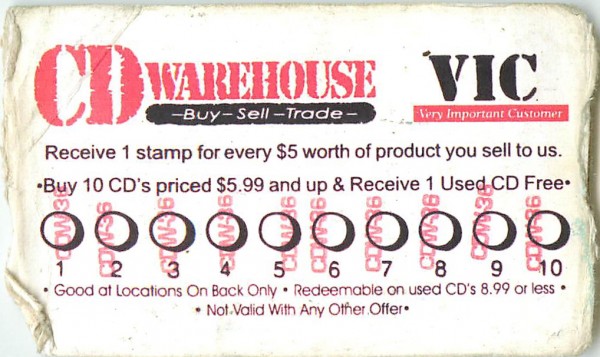

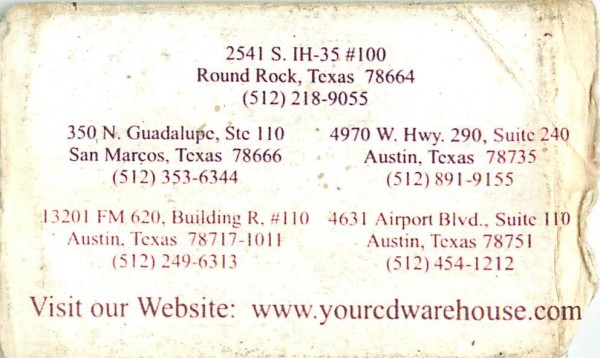

My college self’s idea of evil genius…

…included making counterfeit rewards cards for used CD stores using my then-fancy 600 dpi all-in-one scanner/color inkjet printer, my student-licensed copy of Photoshop, and some Avery printable business card paper. I’d bought one CD, getting one card and one stamp, then used Photoshop to extract the stamp image and duplicate it nine more times. I don’t think I ever actually tried to pass one of these, but I could have. Which was the whole point, I think: “First, a free used CD worth $8.99 or less, then the world!“